Andrew R. Brown

One of the great things about music is that it is multifaceted. It can be many things to many people, and you can spend a lifetime studying it but still not be close to a complete understanding. So what does it mean to have developed musicianship or to be musically trained? Likely it means different things in different contexts, but we can expect there to be some areas of commonality about a musician’s ability to perceive, understand and create sonic experiences. As educators, we should be asking questions about how to define and develop musicianship as we prepare programs of music instruction for our students.

There is a tradition of musicianship training in Australian schools and universities that focuses on aural and written music theory skills. In this article I wish to encourage a broader view of musicianship than that; one which takes account of the many aspects of musical proficiency as they exist in a globalised and diverse musical world, and one that is inclusive of old and new music technologies and practices.

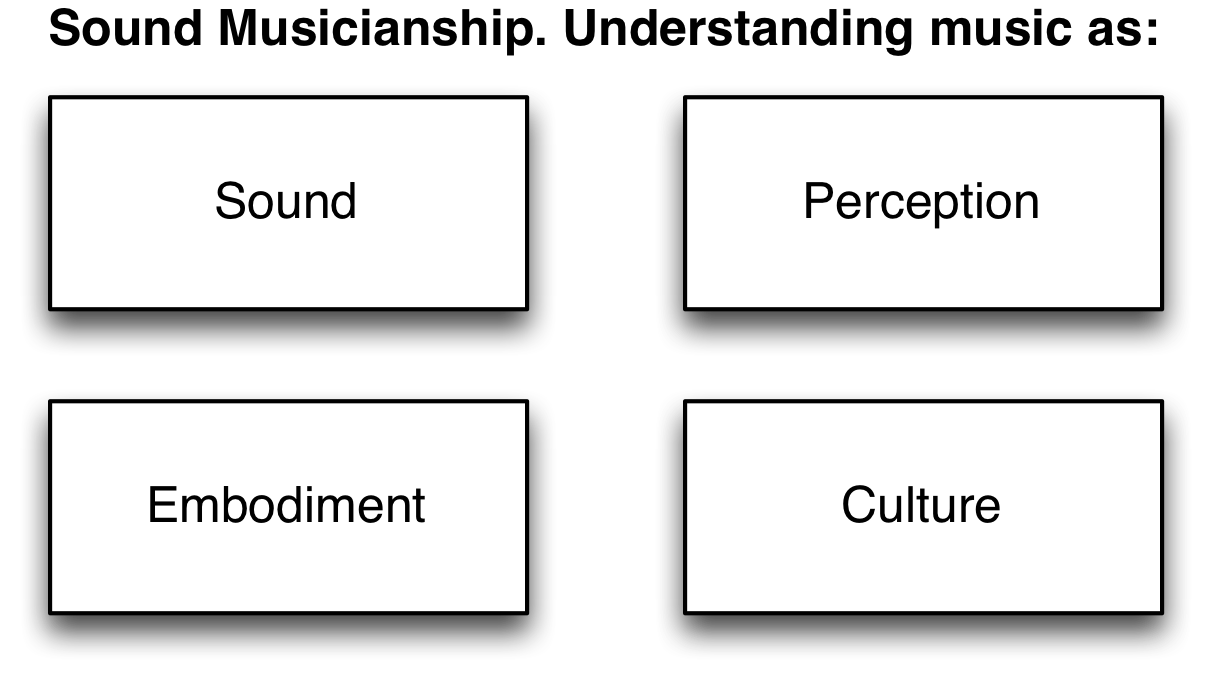

This article explores musicianship from four perspectives—sound, perception, embodiment and culture—in the hope that this framework stimulates a reconsideration of musicianship and how it might be developed.

Music is a discipline that is primarily concerned with the medium of sound. Acknowledging this, music is often described as ‘organised sound’. It seems reasonable then that a central aspect of musicianship should be an understanding of music as sound. Appreciating how the acoustic properties of music, such as timbre, duration, pitch, loudness, and directionality are important fundamentals for musicianship. The examination of music as sound, and the consideration of musicianship as the craft of listening to and making sound, provides a reasonably neutral basis for the study of many musical genres, cultures, and practices. Such a study would include the principles of acoustics, how instruments, voices and loudspeakers produce sound, and would also examine properties of the harmonic series which are a doorway to explorations of timbre, harmony and rhythm. In addition, since music is often distributed as sound objects through audio recording and digital data transfer, a working knowledge of these processes has become essential for modern musicians.

An educative focus on sound can be achieved through activities such as spectral analysis, deep listening activities and sound walks, audio recording projects, and instrument making. In activities such as these we can explore the sonic properties of sound objects, their placement in the world around us, and their expressive potential.

Music is heard or imagined and has psychological and emotional features. Investigating how music is heard and understood has been an active area of research in recent decades, and the fields of music perception and neuroscience are providing many new insights into music and how we appreciate it. While music often exists as sound waves in the world, it also exists as experiences in the mind and body. Music is heard, interpreted, and has psychological and emotional dimensions. Musicianship studies have long acknowledged this and aural awareness plays a significant part in musicianship training as a result. There are many opportunities for embracing sonic perception and awareness as a basis for musicianship that embrace the ways in which our hearing and our brain interpret sonic and musical contexts. As well as a recognition of music elements like pitch and rhythm, studies in this area can include higher order properties such as expectation, closure, tension, release, texture, density, complexity, and so on.

Music can also be imagined (not simply heard) and this highlights the relationship between the brain and music, which is an increasingly popular topic. Having an understanding of hearing, perception, neurology, psychoacoustics, imagination, memory, acoustic ecology and so on can contribute to a well-rounded music education. The relationship between externalised musical sounds and inner hearing can be explored by students in a number of ways; through aural analysis and other listening tasks, through the study of compositional techniques that rely on perceptual effects like grouping, streaming and masking, or using synthesizers to recreate imagined sounds.

Music making is a holistic bodily experience and an activity that involves the coordination of bodily gestures and sounds. Just as understanding music as sound and thought are critical, so is developing an embodied understanding. The connection between gesture and music is obvious at one level; sounds on instruments are largely generated and controlled through human gestures and musical understanding is importantly demonstrated through action. Embodied musicality is also relevant in less obvious situations like audiation practice where imaging yourself performing can assist motor skills.

The development of gestural performance capabilities on musical instruments or through singing are traditional aspects of musicianship but, it should be noted, the definition of musical instrument performance is continually extending, and these days includes practices like DJ’s manipulating turntables, game console control of music games, and live coding on laptops.

In addition to instrumental performance and singing, other activities where students achieve embodied musical experiences can include conducting an ensemble, live mixing at an audio console, tapping rhythms, walking in time with a musical pulse, performing with a MIDI control surface, or dancing to music.

Music making and appreciation have important social and cultural dimensions. As well as involving personal experiences and expression, music is often made in groups and appreciated at concerts and festivals with others. Music plays various roles in celebrations, rituals and other community occasions. These roles vary between societies, communities and subcultures. A well-rounded musicianship includes an awareness of music’s social and cultural dimensions, and the skills to participate in, manage and lead these activities. A meaningful engagement with music is significantly enhanced by a solid understanding of the contextual conditions within which is it made and appreciated.

Musicianship can include skills that don’t directly relate to the making or appreciation of music as sound but are important to operating in society as an effective musician. These include interpersonal, collaborative, leadership and entrepreneurial skills pertinent to particular musical settings. In addition, there are languages, notations, theoretical systems and other technologies that are particular to each musical culture. In music education in Western cultures, as is dominant in Australia, there has been a strong emphasis on fluency in notational and theoretical systems; in particular, stave notation and tonal music theory. In other cultures, different systems are privileged, and even in Western sub-cultures different emphases are evident. For example, Western popular music relies more heavily on aural communication than on notated communication and is heavily reliant on electronic and digital technologies in its workflows.

Looking through these four areas of musicianship, we realise that there is a lot involved with being a musician, and this article has likely only scratched the surface. This is, perhaps, one of the reasons that music is so interesting and that musical lives can be so diverse and so rich. For the educator, this may seem overwhelming; raising an increasingly common problem of the ‘crowded curriculum’. How do we teach all this stuff?

The more pertinent question is; what of all this ‘stuff’ is relevant to teach in our context? Turning this around to the student’s perspective, we might ask: What are the most relevant musicianship understandings and skills a student needs to develop given their interests and aspirations? Acknowledging that a person can’t know everything or do everything, as educators we appreciate that curriculum design involves choices and priorities. There are many stakeholders involved in these choices and many ways of selecting among the options. Students would be empowered to assist in making the decisions about what they learn, in what order and how.

The areas of musicianship outlined here—sound, perception, embodiment and culture—are designed to help guide educational decisions. This framework helps us take a step back from our day-to-day musical activities and avoid the trap of simply doing the things we’ve always done. It provides a perspective from which we can reconsider the priorities of our music programs. From this perspective we can answer questions such as: What aspects of musicianship are or should be relevant? What activities will best lead to developing them? A utility of this framework is how it can help us maintain a balance between these four areas of musicianship. We need to avoid a preoccupation with, or neglect of, any one area of the framework. To do so would be detrimental to a holistic music education.

The ideas outlined in this article are explored in more detail in the book “Sound Musicianship: Understanding the crafts of music”, edited by the author and published in hard back by Cambridge Scholars Publishing and in electronic form by Exploding Art. The book contains thirty chapters that explore issues relating to the four areas outlined here and several educational case studies. Chapters are written by leading researchers and educators from around the world with a strong representation from Australia.

This text was first published as Brown, Andrew R. 2013. “What Is Musicianship and How Do You Teach It?” Music Forum 19 (4): 44–45 and is based on the edited book: Brown, Andrew R. (Ed) 2012. Sound Musicianship: Understanding the Crafts of Music. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing (available online).

Andrew R. Brown is a musician, educator, researcher, designer, software developer and author. His professional interests revolve around technologies that support creativity and learning. Andrew’s creative activities focus on digital audio-visual works using generative processes and interactive musical performances with computers including live coding; visit http://andrewrbrown.net.au. He is Professor of Digital Arts at Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia.